A new report by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has found the majority of debit card overdraft fees are incurred on transactions of $24 or less and that the majority of overdrafts are repaid within three days. Put in lending terms, if a consumer borrowed $24 for three days and paid the median overdraft fee of $34, such a loan would carry a 17,000 percent annual percentage rate (APR).

“Today’s report shows that consumers who opt in to overdraft coverage put themselves at serious risk when they use their debit card,” said CFPB Director Richard Cordray. “Despite recent regulatory and industry changes, overdrafts continue to impose heavy costs on consumers who have low account balances and no cushion for error. Overdraft fees should not be ‘gotchas’ when people use their debit cards.”

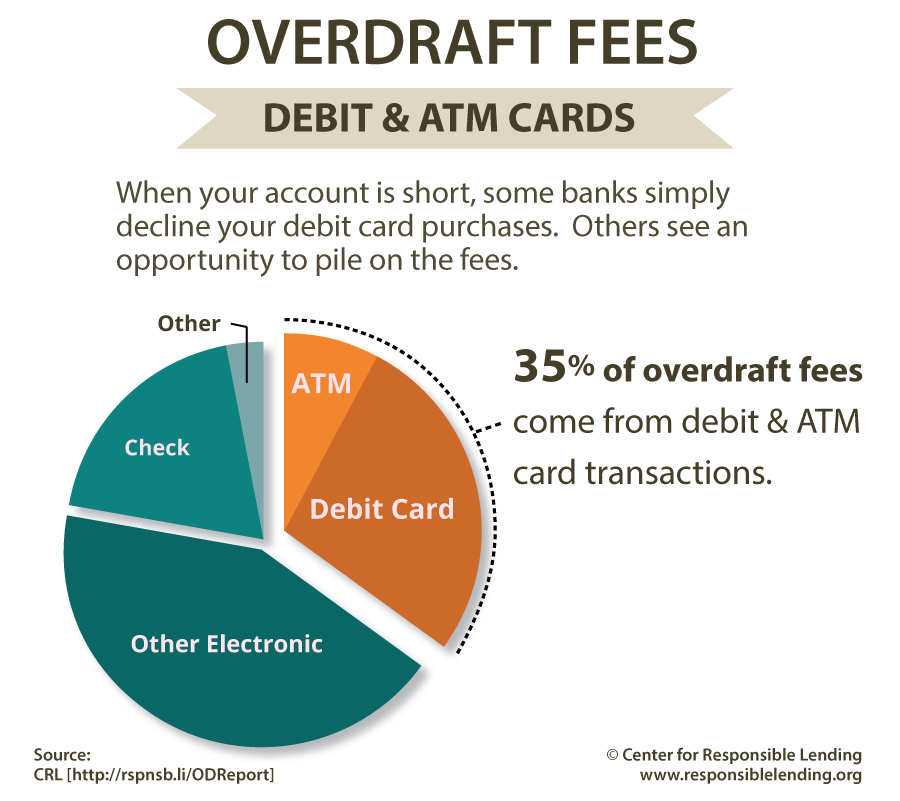

An overdraft occurs when a consumer doesn’t have enough money in his or her checking account to cover a transaction, but the bank or credit union pays the transaction anyway. This practice can provide consumers with needed access to funds. Financial institutions typically charge a high fee for this service in addition to requiring repayment of the deficit in the account. A consumer can overdraw his or her account through checks, ATM transactions, debit card purchases, automatic bill payments, or direct debits from lenders or other billers.

In 2010, federal regulators put in place a new “opt in” requirement that depository institutions obtain a consumer’s consent before charging fees for allowing overdrafts on most ATM and debit card transactions. Opting in for overdraft coverage does not apply to checks or automated payments, known as Automated Clearing House (ACH) payments. For these, the bank can choose to not cover the transaction and reject the check or automated payment; this usually results in a non-sufficient funds (NSF) fee. Or, if the bank chooses to cover the difference, it can charge the consumer an overdraft fee – regardless of whether that consumer opted in for the debit card coverage.

In addition to the regulatory changes, financial institutions have also updated their overdraft policies in recent years. For example, some banks and credit unions do not charge an overdraft fee if the consumer is only overdrawing on his or her account by a small amount, such as $5. Some institutions also cap the number of overdraft and NSF fees they will charge on an account on a single day.

Today’s study raises concerns that despite these recent changes, a small number of consumers are paying large amounts for overdraft, often for advances of small amounts of money for short periods of time. Today’s report finds that among the banks in the study, overdraft and NSF fees represent more than half of the fee income on consumer checking accounts. The study found that about 8 percent of accounts incur the vast majority of overdraft fees.

Specifically, the report found:

- Consumers use debit cards nearly three times more than writing checks or paying bills online: The most common way consumers access money in their accounts is through debit card transactions. The study found that consumers use their debit cards for purchases about 17 times a month; in comparison, consumers, on average, write checks fewer than three times per month, and they make automatic bill payments a little more than three times per month. Consumers who are opted in for overdraft services use their debit cards even more frequently, at 24 times per month. The wide use of debit cards can mean more fees for those who opt in for overdraft.

- Majority of debit card overdraft fees incurred on transactions of $24 or less: When consumers use their cards, it is typically for smaller purchases than when they write checks or use a bank teller. Consumers who opt in for overdraft services incur the majority of their debit card overdraft fees on transactions of $24 or less. Most overdraft transactions for which a fee is charged — including debit overdraft transactions — are $50 or less.

- More than half of consumers pay back negative balances within three days: Most consumers who overdraw on their accounts bring their accounts to a positive balance quickly. More than half become positive within three days; and more than 75 percent become positive within a week.

- Consumers pay high costs for overdraft “advances:” Overdraft fees can be an expensive way to manage a checking account. The median overdraft fee at the banks studied was $34. If a consumer were to borrow $24 for three days and pay a $34 finance charge, such a loan would carry a 17,000 percent APR.

- Nearly one in five opted-in consumers overdrafts more than ten times per year: The study found that 18 percent of opted-in accounts overdraft more than ten times per year, compared to 6 percent for non-opted-in accounts. In addition, opted-in accounts are nearly twice as likely to have at least one overdraft transaction per year. Not all of these overdrafts incur overdraft fees, but many do.

- Opted-in consumers pay seven times more in overdraft and NSF fees per year: Consumers who opt-in for overdraft fee services are paying significantly more for their checking accounts than non-opted-in consumers – about seven times more in overdraft and NSF fees. On average, opted-in accounts pay almost $260 per year in overdraft and NSF fees compared to just over $35 for non-opted-in accounts.

Today’s study is based on data from a set of large banks supervised by the CFPB. The CFPB examined account-level and transaction-level data – which did not contain consumers’ directly identifying personal information – to better understand how overdraft practices affect consumers. The study reflects a significant portion of U.S. consumer checking accounts. The study was supplemented by other research and responses to a CFPB Request for Information issued to the public in February 2012.

A report by the CFPB last year raised concerns about whether overdraft costs can be anticipated and avoided by consumers. The report showed big differences across financial institutions when it comes to overdraft coverage on debit card transactions and ATM withdrawals, drawing into question how banks sell the overdraft account feature. The report also found that consumers who opt in end up with more costs and involuntary account closures.

The CFPB reports are intended to further the Bureau’s objective of providing an evidence-based perspective on consumer financial markets, consumer behavior, and regulations to inform the public discourse. The CFPB plans further studies on how overdraft works and how it is affecting consumers. The Bureau is also weighing what consumer protections are necessary for overdraft and related services.

Thanks for reading CPA Practice Advisor!

Subscribe Already registered? Log In

Need more information? Read the FAQs

Tags: Financial Planning